Developer: Ninja Theory

Publisher: Ninja Theory

ESRB Rating: M (Mature)

Platforms: PlayStation 4 [reviewed], Xbox One, PC

Development studio Ninja Theory is known for its experience in the big-budget, AAA gaming space; over the years, they’ve worked with a wide variety of publishers, and have crafted a number of well received action games, establishing themselves as a talented group of people. With their newest game, Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, Ninja Theory has taken on an ambitious task that puts all of that talent to the test in new ways. Unlike with their other games, Ninja Theory self-published Hellblade, taking on all the extra work that a publisher would do, and creating the game with a much smaller budget as well. On top of that, Hellblade attempts to do what few other games have dared: to portray what it’s like to live with psychosis. It’s an admirable but undeniably daunting goal. So, the question is: does Ninja Theory succeed?

Hellblade tells the story of a young Celtic woman named Senua who is travelling into the underworld to recover the soul of her slain lover, Dillion. Senua suffers from severe mental illness, however, which alters her perception of reality: she hears voices, she sees runes and patterns in the world where none exist, and can even lose control of her body to one of the other personalities existing within her mind. It’s a fascinating premise for a story, and the stellar performance by the lead actress really sells the raw agony and struggle that Senua endures throughout her journey (which is particularly impressive since the actress didn’t come into this project with any professional acting experience).

The game starts without much build-up; after some brief exposition to establish Senua’s mental illness, you are dumped onto the shore of the underworld and set on your path. Senua’s backstory, which is crucial to understanding both her and her quest, are pieced together over the course of the game. But even as the player is provided answers, more questions arise: can she trust any of the voices she is hearing in her mind? How much of what Senua perceives is real? Interestingly, it wasn’t until I finished the game and watched the featurette that comes with it (which the player is warned not to watch until completing the game) that I got a better understanding of the story, and, relatedly, of the ways that Ninja Theory sought to portray mental illness. Some of the ways they showed the effects of psychosis had been lost on me during the actual gameplay, and in retrospect, I wish that this information could have been given to the player before or during the game, rather than just at the end.

If there’s one aspect of the game that Ninja Theory absolutely nailed, it’s the visual presentation. You can’t tell that this game was made on a small budget just by looking at it: the realistic lighting, gritty hellish landscapes, and plethora of other graphical effects show just how much experience the developer has in making top notch visuals that can stand up against any AAA competitor. The face capture they used for Senua stands out in particular, as every ounce of emotion given to the character by the actress is recreated in painstaking detail on Senua’s face. While it may seem superficial, this level of detail goes a long way in establishing the emotional weight within Senua and within the story as a whole.

Alongside the gorgeous visuals, the audio work is also one of the game’s highlights. Every time you boot up the game, a message appears onscreen encouraging you to play with headphones on, and upon starting the journey you quickly find out why: Senua often hears voices in her head throughout her journey, and hearing those voices yourself, right next to your own ears, is an integral part of the player’s own experience. Sometimes the voices are encouraging or helpful, alerting you to an enemy that’s about to strike you from behind; other times the voices are despondent, bemoaning Senua’s situation; still other times they mock Senua, causing her (and by extension, you) to question her perception of reality. It’s as if all the thoughts you would normally experience as your own have now become their own personalities in your mind, bombarding you constantly without your consent.

In terms of the actual gameplay, you spend most of your time alternating between combat sequences and puzzle solving. In the combat sections you square off against enemies armed with various melee weapons – swords, maces, axes, shields, etc. – and to beat them you’ll have to learn their attack patterns and strike them with your sword when they’re vulnerable. The enemies are slow to approach you and flank you, but they can do some serious damage with just a couple hits, so it’s important not to let yourself get surrounded. Early in the game, only one or two enemies will appear at the same time, but later on you’ll have to deal with four or more, each with different attack patterns to take into account. At its best moments, the combat feels downright exhilarating; the controls are smooth, the character animations are fluid and appropriately stylized, and landing a successful parry is one of the best feelings I’ve had in an action game.

The puzzle sequences in Hellblade feature some of the most creative ways that the developers portray the effects of psychosis. One of the most common puzzles, for example, is to find runes in the environment: a door will be locked until you can find several shapes that appear in the game world, requiring you to line the camera up with doors, shadows, wooden posts, and other objects until you can see the shape of the various runes. This puzzle is designed to mimic the way that real people with psychosis will often see shapes and patterns in the world, where the rest of us would just see coincidence. Other puzzles in the game also make use of camera positioning, and every now and then you’ll encounter a puzzle that throws in another twist, such as a section shrouded in darkness that forces you to focus on different senses in order to survive.

It’s in the gameplay that you can start to see the game’s shortcomings, and the limitations Ninja Theory faced because of their smaller budget. While all the gameplay present is slick and well polished, the problem is that there’s not enough variety. Certain puzzles (such as the rune puzzle mentioned above) get reused too often in the game, and thus become less interesting over time. The combat sequences are enjoyable in a visceral sense, but they’re also repetitive and formulaic: dodge or parry an attack, land some hits of your own, rinse and repeat until victorious. New enemy types require you to memorize a few new attack patterns, but it’s not enough to make the combat truly interesting. And the game is linear to a fault. Many puzzles don’t really require much thought; to solve a puzzle, all you often have to do is follow the main pathway to a few specific spots on the map, and you’ll find your solution. There just isn’t much in the way of critical thinking required to solve the puzzles, which detracts from their appeal. Even considering the game’s relatively short length (6-8 hours for a full playthrough), this lack of variety still holds the game back.

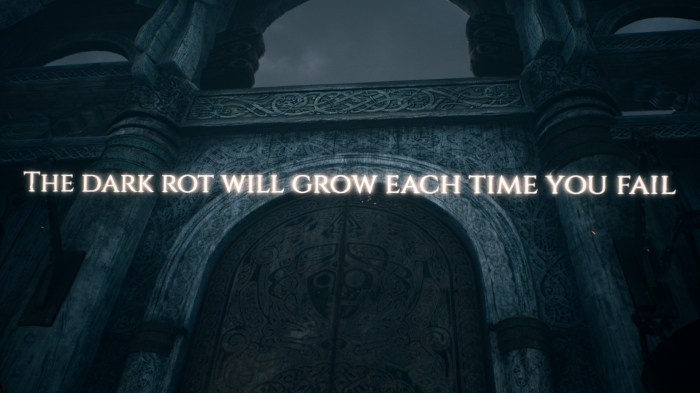

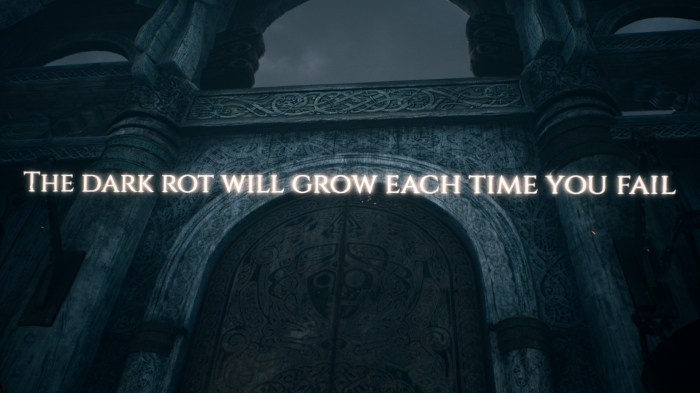

And then there’s the issue of character death. During your first combat encounter early in the game, you are faced with enemies you cannot defeat, leading to your first death. Text then appears on the screen informing you that a “rot” has entered Senua, and with each death it will grow up her arm and closer to her head. If it reaches her head, her journey will be over, you’ll lose all progress and have to start the game over from scratch. This game mechanic, often called “permadeath”, is intended to add pressure to the combat sequences and encourage the player to fight cautiously. It isn’t commonly used in very many games, certainly not story-heavy action games like this, which helps Hellblade stand out. Or at least, that’s what Ninja Theory wanted people to think.

When other journalistic outlets published their reviews just prior to the game’s release in summer 2017, they generally took for granted that the permadeath mechanic was real. Once everyone got their hands on the game, however, it was soon discovered that the mechanic was a bluff, or to be less charitable, a lie; you could die as many times as you wanted to, but the rot would never make its way to Senua’s head. People debated over why Ninja Theory would do this, with many concluding that it fed into the theme of mental illness, as the player would be scared of something that wasn’t actually real (the game’s lead developer has since given a very brief statement regarding this decision). Since I picked up the game only recently, however, I was already aware of the game’s deception going into it, and thus I could only imagine the tension that those first players would have felt when they played Hellblade last year. One time during my own playthrough, I actually saw the rot retreat much further down her arm after one of my deaths, which only served to further break my immersion.

So with all this in mind, what does one make of Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice? It seems to me that it can be evaluated from a couple of different angles. As a method of portraying mental illness, the game is an unparalleled success. A wide variety of psychosis symptoms are effectively incorporated into the game, in some ways playing directly into the interactive element that only a game can achieve. And you don’t have to take my word for it, either: as this Accolades Trailer shows, Ninja Theory has received hundreds of letters from actual sufferers of mental illness, letters saying that this game has done a better job portraying their situations than any book or other work of art before it.

As a video game, however, Hellblade is more of a mixed bag. On one hand, the incredible audio/visual presentation, stunning performance by Senua’s actress, and the combat’s raw, visceral appeal all work to elevate the experience; on the other hand, the linear design, simplistic gameplay, and overused puzzles hold the game down. I can’t help but feel that there is missed potential here, and that the game’s limited budget kept the team from putting as much depth into the gameplay as they did with the story and thematic elements.

Ultimately, I enjoyed my time with Hellblade. The game’s simplicity keeps it from greatness to an extent, but the things that it does well manage to offset its shortcomings. Perhaps more importantly, though, Hellblade gave me a window into the lives of people much different from myself. My knowledge of mental illness going into this game was negligible, since neither I nor any of my closest friends or family suffer from it; now that I’ve played Hellblade, I have a better understanding of how mental illness affects people, and the incredible strength of those who have lived through it and endured.